Every Saturday at 8 a.m., no matter the weather, Chris Pomfret sets up a dozen or so big garbage cans outside his church in Algiers Point on New Orleans’ west bank. Glass clinks and clatters as neighborhood residents come and go with their empty bottles — mostly wine, beer and liquor bottles.

"New Orleans has a good time with their drinks," Pomfret said with a laugh.

This weekly ritual started back in 2019 as a small project at Mount Olivet Episcopal Church. The city hasn’t had a dedicated glass recycling program since Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Residents can bring their glass to a recycling drop-off site on Elysian Fields Avenue, but only on Saturdays and only up to 50 pounds.

For the people in Algiers Point, Pomfret’s operation fills a gap. By 1 p.m., the bins will be filled with about a thousand pounds of glass.

“It's like a farmer with his herd of cows, they've got to be milked every day,” Pomfret said. “This has to happen every week, no matter what, because the public expects it.”

Each full bin weighs about 70 pounds — Pomfret said he weighed them once — so they’re heavy and difficult to load into the small, beat-up red pickup called “Cupcake” that Pomfret and his team of volunteers use to transport the glass. But knowing where it’s going makes the effort worth it.

“At least we know that it's going to a worthy home that's the best it can be for the environment," Pomfret said.

‘Why don’t we do something about this?’

That "worthy home" is Glass Half Full's processing facility in Chalmette, where trucks arrive loaded with thousands of pounds of glass from across Louisiana, Mississippi and even Alabama. The company turns the glass into sand that’s used to help rebuild Louisiana’s disappearing coastline, which loses about a football field’s worth of land every 100 minutes.

Franziska Trautmann and her co-founder, Max Steitz, started the operation in early 2020 when they were seniors at Tulane University — after sharing a bottle of wine one evening.

"We realized that it would end up in a landfill because there was pretty much no glass recycling in New Orleans," Trautmann recalls. "We were in this weird phase, we're going to be graduating soon, what are we doing with our lives. And we said, why don't we do something about this?"

They thought it would be a small pet project. Then the pandemic hit, and they had a lot more time on their hands. And with bars and restaurants closed, New Orleanians were drinking more at home — and accumulating a lot of glass bottles.

They started in a backyard with a tiny machine that could process one bottle at a time. That machine now sits in a corner of the new facility like a museum piece, unassuming beneath a network of giant machinery.

A single wine bottle — about a pound — creates roughly a handful of sand for coastal restoration. But some of that recycled glass is taking a different journey this year — one that ends at the parade route.

Throws ‘become more precious’

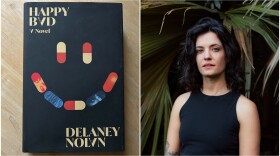

Trautmann is the 2026 Queen of Krewe du Vieux, the raunchy, satirical parade that traditionally rolls through the French Quarter and Marigny during Carnival season in the lead up to Mardi Gras. The theme this year is "Save the Wet Glands" — characteristically lewd wordplay on Louisiana's wetlands crisis.

Trautmann used her reign to make a statement about sustainable Mardi Gras.

"My message is that we can keep our culture, have fun, and still make the world and the environment a better place," she said.

She threw recycled glass beads — keychains, necklaces and bracelets — made by local artist Andrew Barrows from bottles collected around the city: dark blue beads made from Bud Light Platinum and Sky Vodka bottles, lighter blue from Bombay Sapphire gin.

For Trautmann, it's about more than just environmental responsibility. It's about returning to Mardi Gras roots.

“Glass has always been around, literally, since ancient times,” she said. "Plastic is the new thing, so yes, we are returning to our actual roots. And we used to have all glass beads. We used to have less throws."

Arthur Hardy, the Mardi Gras historian who's been publishing his annual parade guide for 50 years, confirms this history. In his Mid-City home, he pulled out samples from his collection — glass beads from the 1950s and 60s.

"Many of those were made in Czechoslovakia, and they were glass," Hardy said. "They went out of vogue in the early ‘70s and were replaced by plastic. It was cheaper, but then it got to be way over the top, too much."

Hardy admitted he was skeptical when the movement for more sustainable throws started about a decade ago.

"I was one of the people who said publicly, I'm not sure this is going to work," he said. “I was wrong. I was never against the movement, but I just didn't think it was going to take root. But it has, tremendously."

Now, he sees more krewes moving toward recyclable and locally-sourced throws. Rex, for instance, requires members to buy packages that include locally-sourced and environmentally-friendly items. Krewe of Freret banned plastic beads last year.

Hardy sees the shift toward quality over quantity as positive for the entire celebration, though he acknowledges the challenge of changing expectations. People want to catch a lot of throws at parades, Hardy said.

“But if we decide to throw fewer things, they become more precious and more collectible,” he said. “And don't wind up in the catch basins.”

‘There’s nothing more quintessential New Orleans’

Glass Half Full also participates in Recycle Dat, a coalition working to make Mardi Gras more sustainable, with collection points along various parade routes. After Krewe du Vieux, paid staff and volunteers followed behind to pick up recyclable materials.

For Trautmann, the plastic bead problem goes far beyond just waste in the streets.

"They're made in factories with very poor working conditions and using materials like lead that are extremely toxic to people," she said. "So it's the workers that are making them, then it's shipped over to us from across the world. We throw them, they pollute our bodies, and then they pollute our environment and our waterways."

The foundation of Mardi Gras isn’t plastic throws, Trautmann said. It’s the community coming together. It’s about experiencing joy, despite whatever is going on in the world outside of Carnival.

That’s something residents, like Pomfret, agree with. And he loved the idea that the glass they collect every Saturday — rain or shine — might end up as beads at a parade.

“The whole thought of that, that the glass that we collect here ends up being a Mardi Gras throw, I think it's just wonderful,” Pomfret said. “I mean, going to the coastline is great, especially when we have erosion and all the sea levels rising, but to make it a Mardi Gras throw, there's nothing more quintessential than that for New Orleans."

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.