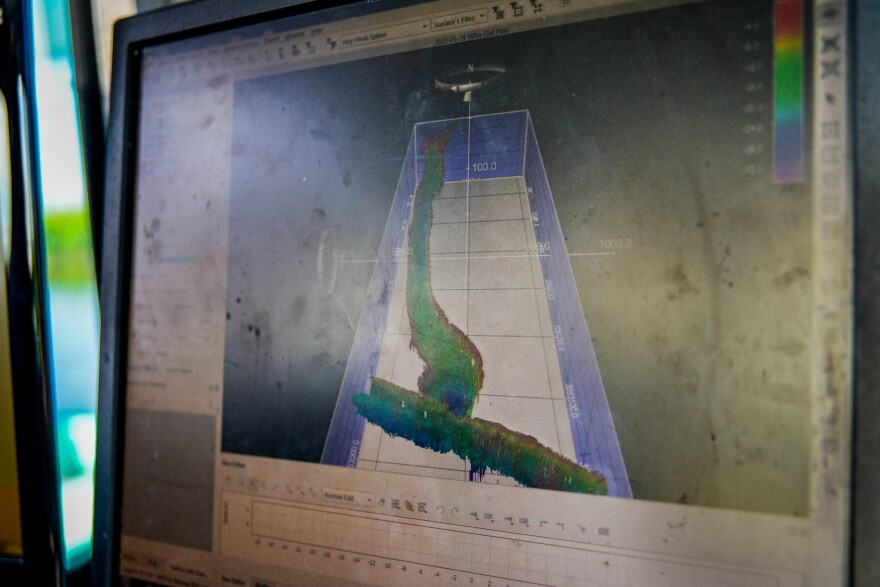

Fifty-five miles south of New Orleans, geologist Alex Kolker and surveyor Dallon Weathers tinkered with their computer while floating near the marshes on Plaquemines Parish’s east bank. A long arm extended from the boat, a tool that sent out thousands of points to map its surroundings.

They docked inside a newly-formed channel directly across the Mississippi River from the small town of Buras. Where a wall of rocks once stood, the river forced its way through, scattering the rocks below the water’s surface and scouring out the bottom to create a nearly 90-foot-deep crater near its opening.

“To some extent, it was just that the force of the river was so great that it overwhelmed the rocks,” said Kolker on the boat. “What caused that? I’m not sure.”

Now, a waterway once known as Bayou Tortillon has grown sixfold within just three years from what was once a narrow outlet, according to the pair’s recent technical report.

At 850-feet wide, it now carries about a sixth of the river’s flow, diverting it into Quarantine Bay. Combined with other cuts in the bank within this 8-mile stretch of the river, about a third of the river is now flowing through the east bank.

“That’s something of a reorientation of the flow of the river,” Kolker said.

For some, the channel — referred to as Neptune Pass by federal and state officials — presents an opportunity for research and coastal restoration as Louisiana’s protective wetlands continue to slip away. But as more water branches off from the river’s main stem, a slower Mississippi River could pose navigational challenges for the oceangoing vessels that traverse the ship channel.

Within recent months, all levels of government have turned their attention to the crevasse as it continues to grow and widen, eroding the river bank. All of the discussion centers on one question: what do we do with it?

Over the years, the Corps has faced criticism for prioritizing navigational needs above all else, sometimes over those of the environment.

Coasting through the crevasse, Plaquemines Parish Council member Richie Blink keeps tabs on the water depth with sonar on his own boat. Chugging into Quarantine Bay, he watches as the area grows shallow. The boat approaches an old oil platform, and Blink steps off the boat — into the water.

Where the bay was once 8 feet, it’s just now just two, with new sediment piling up behind the legs. For him, the shoaling and, to a greater extent, the channel’s formation exemplifies the dynamic nature of Louisiana’s coast.

“This cut opening up is probably a symptom of greater changes, right? It's not just lack of maintenance, but the river itself is changing,” he said, pointing to higher river years as another example.

Blink hoped to send that message when the Parish Council passed his ordinance to rename the cut Avulsion Pass in late May. An avulsion refers to a change in the river’s course.

Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority Executive Director Bren Haase agreed. As the land sinks and sea levels rise, the Corps has already had to adjust where it dredges to maintain the depth needed in the ship channel.

“The only constant here really is change, and that's kind of a truism for all coastal Louisiana,” Haase said.

That’s why the state and Blink have encouraged the Corps to consider ways to maintain the connection between Quarantine Bay and the river, after aerial images suggested that the start of a new delta could be forming. A new delta could mean more land, and more opportunity to study land formation at a flow unmatched across much of the coast.

“We don’t have too many good examples of large deltas that we’ve watched built,” Kolker said.

Currently, the best example is the Wax Lake Delta, south of Morgan City, where an outlet formed in the 1940s started building a delta 10 years later, and scientists have since been able to study that emergence and development. On average, 126,000 cubic feet of water flow through the Wax Lake Outlet, nearly the same as the new river cut.

This cut, though, would give researchers a chance to study a large, emerging delta in real time, Kolker said.

But shoaling just downriver from the cut has made the cut a threat to the Corps’ primary focus: navigation. In mid-May, the Corps dredged the channel as a result of the slowed flow of the Mississippi from the channel. And adding more areas for the agency to dredge adds more cost, said spokesman Ricky Boyett.

For now, the Corps plans to lay a “rock blanket” on the channel’s banks to prevent further erosion and widening. But Boyett said the agency is working to design a way to at least partially close the crevasse by the fall.

That could look like building another rock structure placed a half mile into the channel that blocks the river’s flow, leaving about 10 feet of water on top to allow for small boats to pass.

While the sediment carried by the river water into Quarantine Bay isn’t the Corps’ priority, Boyett said they’re trying to find a solution that stops the cut from growing, holds back enough river water to prevent sandbars but still allows some of the mud, silt and sand to pass through to the other side.

“Priority one that will drive all final decisions is the navigation that uses the deep draft channel,” Boyett said. “But if we can do things that are still beneficial to the environment and help recreation without hurting priority one, then we’re going to.”

Long before the cut opened, the state had pressed the Corps for more flexibility and consideration for restoration while carrying out its mission. Right now, legislation working its way through Congress would authorize a comprehensive study of the lower Mississippi River to potentially rethink the best tactics for managing the ecosystem, flooding and navigation on an ever-changing waterway.

With more intense storms, heavier rain and continued subsidence expected in the future, Haase said the study intends to answer “what really is the best way to sustain and maintain the river.”

For the crevasse, Blink and Haase have suggested alternative solutions to the Corps, from installing a weir, or low dam, for closure or even looking to other areas in that stretch of the east bank to close off and add flow back to the river.

“It’s a math problem, right?” Haase said.

Back on the boat, Blink said he often feels like he’s flying a plane into a crash as environmental challenges pile up for his parish amid the state’s land loss crisis and global warming. Like the river, the world is changing, he said, and a more fluid approach is needed.

“The policies need to be flexible enough for the Corps to do their job in a 21st century manner,” he said. “It’s not the Corp’s fault that they’re bound by these rules, but we need to update.”